By Paul L Dunwell writing for Kompass UK

Executive Summary:

It would be easy for the uninitiated to automatically assume that convoluted international supply-chains are risk-laden logistical nightmares which cannot be worth their while. Certainly those who have shallow pockets and/or are risk-averse might be best not to entertain the notion of developing one – or even consider being a link in such a chain. Yet fortune favours the brave. This well-researched piece explains, in simple terms, with some intriguing insights including how one small business muscled their way into a lucrative chain supplying vehicle parts. We also consider the key advantages and disadvantages of throwing one’s supply-chain net a little wider, and where to obtain a hefty lever.

Is this just an excuse to hype the undeniable potential of Kompass databases?

No. That’s incidental. To cite a respected authority with gravitas, The Institute of Supply Management told the audience at their 89th Annual International Supply Management Conference that ‘what most companies and industry analysts fail to realise is that “big and complex” can prove to be more profitable than “small and simple”‘ (from ‘Challenges of Complexity in Global Manufacturing Insights to Effective Supply Chain Management, Growth and Profitability‘).

Indeed many successful companies like BMW have been happily running the aforementioned ‘big and complex’ systems for years, though adjustments to operations – or indeed their continuation – will remain predominantly event-driven. Some of the contenders, in terms of contemporary events which might push change, include (but are by no means limited to):

- The ongoing wrangles over Brexit which have called into question the potential impact of leaving the EU, the single market and the customs union.

- The potential trade war between the USA and China, one that could impact the UK according to The Guardian, which tells us that ‘trade barriers would not only damage both countries but would also disrupt global supply chains, raising prices for customers worldwide‘. Consider Walmart, the largest retailer in the world, importer of numerous Chinese goods, and how it effectively owns the UK supermarket chain Asda (via Corinth Services).

- Companies such as Apple, investing in both the USA and China, would be hurt too. Incidentally Apple has already had supply-chain problems with iPhones made in China by Foxconn, which was tainted by ‘sweatshop’ claims and worker suicides.

- The threatened withdrawal of the USA from the 12-nation Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) which President Trump previously bragged he’d destroy, although he is now rethinking that strategy. Likewise, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) which he wants rewritten. Oh, and Trump might want to pull out of the World Trade Organisation too. Or, there again, he might not.

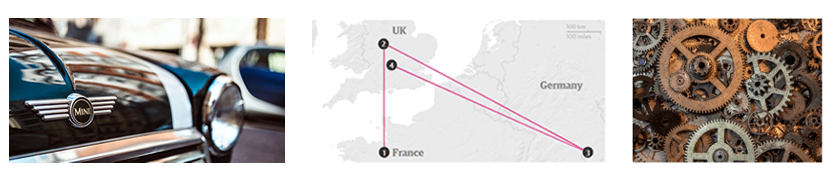

An oft-cited example of complex cross-border co-operation – The Mini crankshaft

Speaking of BMW, you may well be aware of the tale of the life cycle of their Mini crankshaft that travels 2000 miles, repeatedly crossing the English Channel, before it’s sold – see image below. The French cast the rudimentary crankshaft and then we Brits machine it, before sending it to the Germans. They stick the finished crankshaft into the engine, then send it back to us – to insert into the car before it rolls off the production-line. Then in many cases these finished Minis go back overseas to satisfy demand in foreign markets (over the last 17 years, since the Mini revamp, the UK have produced two thirds of the 175,000 that are manufactured annually).

The tale of a BMW Mini part, explained by the Guardian, is not atypical of how businesses with a global reach have capitalised on logistics as complex as any watch movement.

Of course none of this would happen unless the perception at BMW was that such complex cross-border cooperation must be worth the effort and risks. Yet this may change – and events could well drive that change, because in essence the new electric Mini may soon be assembled in Germany or the Netherlands (where a third of Minis are already built anyway) to avoid post-Brexit tariffs. And, should we forget it, BMW could well follow Volvo which announced in July 2017 that it will launch no more ICE vehicles after 2019 since they will all then be electric. In the meantime electric vehicles don’t, as you may realise, have crankshafts. So, in any event, the supply-chain model will most definitely have to evolve.

Where does one start?

Let’s assume that a business has previously made a policy decision that it is going to either develop or expand a complex supply-chain. We have already outlined events that might push change but, meanwhile, other considerations might pull it too. Events which they cannot influence apart, the motivational drivers likely to have been the need to control or reduce costs, to penetrate new markets or innovate. Either way there would be an expectation of increased revenue and enhanced operating profits arising from the change. However quality could well be improved too, especially if a link or links in the supply-chain were to make telling contributions with specialist knowledge and/or skills (think of the unrivaled local knowledge of steel production in the Sheffield area, acquired over centuries, for example), equipment and/or materials, or maybe in some other manner as a consequence of local labour costs, government funding or infrastructural advantages.

All of these gains from the introduction of a more complex supply-chain would, cumulatively, be expected to make a business more competitive that its rivals and then with increased sales it could go on to enjoy the advantages of scale. So with the policy decision taken, the real task becomes a logistical one. If the business is like BMW’s (being massive and geographically disparate) then the supply-chain has to be streamlined, integrated and have multiple controls. But the more integrated a system is, the more it depends on Just in Time (JiT) resourcing and adherence to Total Quality Management (TQM) of all components, processes and products, the more likely it is that the system will fail and – by doing so – precipitate debacles that wipe out any expected benefits. Such risk factors in the supply chain are usually perceived to be three-pronged i.e. environmental, organisational or network related. Yet, whichever direction they come from (and every business is unique), leaders need to manage those risks and indulge in a lot of contingency-planning.

Can we categorise supply-chain risks?

Any inventory is going to miss something – but supply-chain risks are generally regarded to fall within these bounds (some of which are a bit vague, admittedly):

| Capacity constraints | Financial | Labour, production and IT uncertanties |

| Culture differences | Fraud | Supply-demand mismatches |

| Disasters | Terrorism | Sub-optimal organisational interactions |

| Exchange rates | Political instabilities | Principal suppliers going out of business |

| System | Market | Bankruptcy |

| Operational | Business volumes | Public relations, morality and ethical issues |

As you’d expect, some (if not all) of these risks are going to wax and wane in severity according to whether the supply-chain is operating on an entirely local basis or in a global marketplace, but some are real bugbears. Financial risks, for example, often centre on credit-notes and very long waits for payment that may leave some in the supply-chain, especially when it’s international, struggling with their cash-flows and risking insolvency (more on supply-chain financing).

So something goes wrong – what then?

Having back-up plans in case of supply-chain disruptions is crucial. Ask Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC) which in February this year was forced to close many of its 900 branches because it didn’t have any, er, chicken.

Or ask TSB, which this April has had massive IT problems, all a consequence of a failure to contingency-plan, problems that have denied customers access to their accounts and money (though, helpfully, and in a bit of a break with convention, in some cases they’ve allowed ready access to accounts and money belonging to other people).No the TSB debacle isn’t really a supply-chain failure per se, but it ties with KFC in the clueless-management stakes!

Oh and let’s not forget Carillion whose financial director rather ungallantly used a House of Commons committee to heap blame on the supply-chain which arguably had been doing all Carillion’s work.

KFC, Carillion and TSB are three big businesses that failed to generate effective back-up plans which has led, sadly, to massive service-failures.

Intricacy precipitates vulnerability

The devil is in the detail – yet the detail is precisely what senior managers (and financial directors) are paid vast sums to identify, master and neutralise. Sticking with our automotive example, and setting aside Mini camshafts for a moment, there are literally hundreds of thousands of movements when it comes to the components of even a small car. This level of intricacy equates to vulnerabilities that would never normally trouble a more laid-back laissez-faire enterprise. An example? Any compliance issue or tolerance failure in vehicle manufacture could bring the whole system tumbling down. So a company such as BMW has to apply blanket standards that some suppliers may struggle to achieve and/or sustain.

Out of interest, sticking to cars, if you look at Wards Auto, you can see the recall-rates by manufacturer that are a fair reflection on supply-chain efficiency; BMW is significantly below average, and VW is at the bottom of the pile for obvious reasons, whilst Porsche restores some faith in German efficiency by being at the top of the table. Likewise complex systems generate what some may rightly see as needless complications and excessive regulation with which many subcontractors may not wish to comply. Consequently it might be hard to keep compliant suppliers and vendors on-board, and when sources are limited, those suppliers and vendors can call the tune.

Component squeezes are a case in point

Suppliers can always be a pinch-point. Back in 1990 there was an unprecedented demand for ruthenium, a rare platinum-group transition metal, usually used by the electronics industry in an alloy with platinum or palladium, to make wear-resistant contacts for car-parts (as well as IT and armaments).

This unanticipated need for an already-expensive commodity threatened to shut down specialist production-lines around the globe and by implication it would have a knock-on effect along complex supply-chains. This was because ruthenium is ordinarily mined and refined in South Africa, alongside other commodities including zinc and gold, that are all subject to inflexible 5-year plans. What followed in 1990 was an unseemly rush to secure every ounce of ruthenium at any price, a rush that wasn’t lost on opportunist speculators who made matters worse, creating a temporary spike in the price when the metal sold at up to seven times its usual value.

Ruthenium. In 1990 a logistical nightmare owing to its scarcity and importance meant that vital supplies had to be secured at any price.

Can we identify a best-practice approach to mastering supply-chain complexity?

Yes. The following 10-point plan is a simplified derivative, an aide-memoire, of the Institute for Supply Management advice.

| 1. Strategic optimisation | 6. Reactivity |

| 2. Organisation | 7. Utilisation of customers and suppliers alike |

| 3. Synchronisation | 8. Product development |

| 4. Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) | 9. Metrics and conflict resolution |

| 5. Capital | 10. Collaboration |

Do the top performers in supply-chain management fit a typical profile?

Yes they do. Research shows that ‘Complexity Masters’ commonly share three crucial strengths that can be described as:

- An ability to interact with customers as well as suppliers (see point 7 above)

- An ability to generate great and customisable products (see point 8 above)

- An ability to harness technologies (see point 9 above) including those that provide:

– Product Life cycle Management (PLM)

– Advanced Planning Systems (APS)

– Warehousing Management Systems (WMS)

– Transportation Management Systems (TMS)

So what are the rewards for those who master the complexities and negate the risks?

Returning to the advice from The Institute of Supply Management, they also remarked on a Deloitte study (of 600 big businesses across 19 countries in North America and Europe spanning every major industry segment) that identified a small number of global manufacturers whom it dubs ‘Complexity Masters’. This is on account of their apparent ability to manage supply-chain complexity sufficiently well to boost market shares as well as revenues, profits and ROCE. Tellingly this research showed the profit margins of such companies to be an incredible 73% higher than those of rivals with far simpler supply-chains. ‘Thus‘, they say, ‘there is a clear, proven connection between the ability to manage supply chain complexity and overall profitability‘.

Is this just a big-boy’s game?

Not at all. Anybody can do it and here is a lovely example. One of my Anglo-Indian colleagues mentioned in conversation, as I’ve been writing, how she’s recently bumped into a family who have somehow managed to become preferred suppliers of tiny-but-important plastic parts to the motor industry. It’s a great demonstration of how one doesn’t need to be cash-rich to enter a lucrative supply-chain serving a mass-market.

Resham Industries, a tiny outfit in the Punjab run by a chap who can’t speak a word of English, has built a great little business by entering a supply-chain as the manufacturer of simple-to-make fuel pump racks and gear kirloskars (see central panel above) as well as fuel pumps and atomizers for tractors. For further details click here and here (their parts go into these generators).

Conclusions

Anyone looking to develop their supply-chain should be seeking manageable solutions that are sustainable and of benefit to your business. However whilst we may have whetted your appetite, it’s important to remember the key to being successful is finding the right links for your supply-chain. Many businesses are simply happy to be just one link in the supply-chain, in which case they’re also going to have to identify the perfect client-as-consumer (and, in all probability, their own suppliers). If you see business as such a link then, again, you ought to be examining other links with which you could be aligning your business.

Hopefully we’ve provided a little food for thought here, along with some useful check-lists. If your ambitions have been roused by the potential benefits of international supply-chains for your business, Kompass, with detailed company data across 70 countries, may offer the ideal global business data solutions and market intelligence to help you identify prospective contacts, partners & consumers of your products or services – intelligently designed to give you all the leverage you’ll need.

Author: Paul L Dunwell writing for Kompass UK

Disclaimer: Whilst this article is painstakingly researched and substantiated by facts as well as 3rd party opinion, neither Kompass UK or the Kompass Group can accept responsibility for it being used as the basis for any business decisions.

Comentarios

No Comments